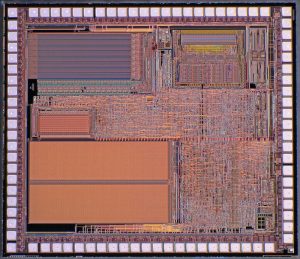

Stratus XA/R (courtesy of the Computer History Museum)

Making the rounds this week is the Computer World story of a Stratus Tech. computer at a parts manufacturer in Michigan. This computer has not had an unscheduled outage in 24-years, which seems rather impressive. Originally installed in 1993 it has served well. In 2010 it was awarded for being the longest serving Stratus computer, then being 17 years. Phil Hogan, who originally installed the computer in 1993, and continues to maintain it to this day said in 2010 “Around Y2K, we thought it might be time to update the hardware, but we just didn’t get around to it” In other words, if it’s not broke, don’t fix it.

Stratus computers are designed very similar to those used in space. The two main difference are: 1) No need for radiation tolerant designs, let’s face it, if radiation tolerance becomes an issue in Michigan, there are things of greater importance than the server crashing and 2) hot swappable components. Nearly everything on a Stratus is hot-swappable. Straus servers of this type are based on an architecture they refer to as pair and spare. Each logical processor is actually made from 4 physical CPU’s. They are arranged in 2 sets of pairs.

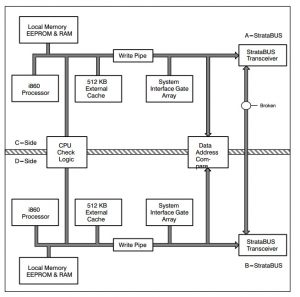

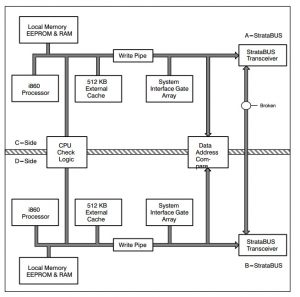

Stratus G860 (XA/R) board diagram. Each board has 2 voting i860. (the pair) and each system has 2 boards (the spare). The XP based systems were similar but had more cache and supported more CPUs.

Each pair executes the exact same code in lock-step. CPU check logic checks the results from each, and if there is a discrepancy, if one CPU comes up with a different result than the other, the system immediately disables that pair and uses the remaining pair. Since both pairs are working at the same time there is no fail-over time delay, it’s seamless and instant. The technician can then pull the mis-behaving processor rack out and replace it, while the system is running. Memory, power supplies, etc all work in similar fashion.

These systems typically are used in areas where downtime is absolutely unacceptable, banking, credit card processing, and other operations are typical. The exact server in this case is a Stratus XA/R 10. This was Stratus’s gap filler. Since their creation in the early 1980’s their servers had been based on Motorola 68k processors, but in the late 1980’s they decided to move to a RISC architecture and chose HP’s PA-RISC. There was a small problem with this, it wasn’t ready, so Stratus developed the XA line to fill in the several years gap it would take. The first XA/R systems became available in early 1991 and cost from $145,000 to over $1 million.

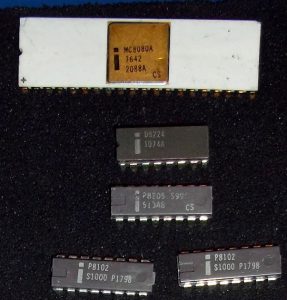

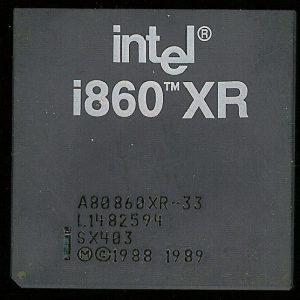

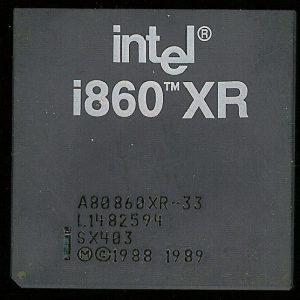

Intel A80860XR-33 – 33MHz as used in the XA/R systems. Could be upgraded to an XP.

The XA is based on another RISC processor, the Intel i860XR/XP. Initial systems were based on 32MHz i860XR processors. The 860XR has 4K of I-cache and 8K of D-cache and typically ran at 33MHz. Stratus speed rating may be based on the effective speed after the CPU check logic is applied or they have downclocked it slightly for reliability. XA/R systems were based on the second generation i860XP. The 860XP ran at 48MHz and had increased cache size (16K/16K) and had some other enhancements as well. These servers continued to be made until the Continuum Product Line (Using Hewlett Packard “PA-RISC” architecture) was released in March of 1995.

This type of redundancy is largely a thing of the past, at least for commercial systems. The use of the cloud for server farms made of hundreds, thousands, and often more computers that are transparent to the user has achieved much the same goal, providing one’s connection to the cloud is also redundant. Mainframes and supercomputers are designed for fault tolerance, but most of it is now handled in software, rather than pure hardware.