ESA Solar Orbiter: When SPARCs Fly

In a few hours (assuming no more delays, UPDATE: Launch Successful) the joint NASA/ESA Solar Orbiter mission will launch on a ULA Atlas 5 Rocket out of Florida, USA. This is a mission a long time coming for the ESA, which like NASA has to get its funding from the government, except in the case of ESA, that involves the governments of many countries in the EU, which can make planning a bit more tricky. The mission was originally baselined in 2011 and hoped to launch in…2013…then 2017..then 2018 and finally a launch date in 2020. The original proposal dates to the late 1990’s as a mission to replace the joint NASA/ESA SOHO Solar mission that had launched in 1995. This creates some interesting design choices for a mission, as designing often happens before a mission is completely approved/funded. For Solar Orbiter this is one of the main reasons for it being powered by a computer that by today’s standards is rather dated, space standards no less!

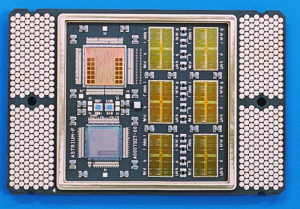

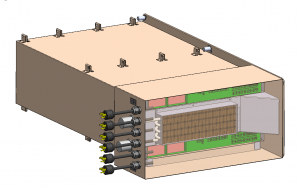

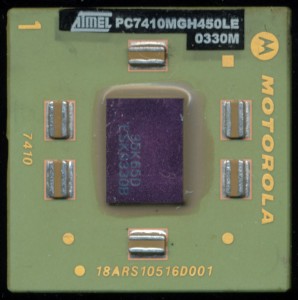

The Solar Orbiter is powered by a processor designed by the ESA, the ERC-32SC. This is the first generation of processors designed by the ESA. It is a SPARC V7 compliant processor running at 25MHz and capable of 20MIPS. The ERC-32SC is a single chip version of the original ERC-32 which was a MCM (Multi chip Module) containing 3 dies that made up the processor (the Atmel/Temic TSC691 Integer Unit TSC692 FPU and TSC693 Memory Controller) that was made on a 0.8u CMOS process. The Single chip version was made possible by a processes shrink to 0.5u. It was also made by Atmel, (whom acquired Temic) and is commercially known as the TSC695 as it is designed for space use, is capable of handling a 300krad Total Ionizing Dose of radiation. The computer used in the Solar Orbiter was built by RUAG and has two seperate ERC-32SC processor systems for redundancy. Each of the ERC-32SCs are actually mounted on a MCM, the single chip SPARC, 48MB of DRAM (38 of which is used, the remainder is for Error Detection/Correction via Reed Solomon method), and a MIL-STD-1553 bus controller/RTC/IO are included in the package.

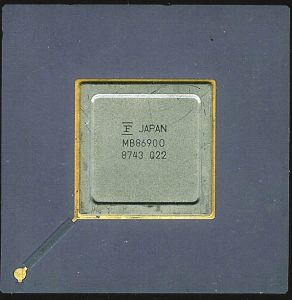

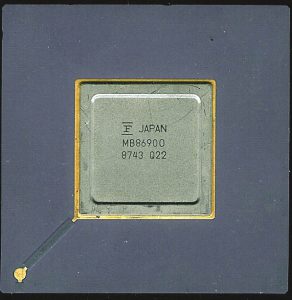

The original specifications for this processor were developed back in the 1990’s, which is why it is a SPARC V7, equivalent to the very first Sun SPARC workstations of the late 1980’s powered by the likes of the Fujitsu MB86900/MB86901. The ESA has developed several follow on processors since, all based on the later SPARC V8 architecture. They are faster, and more efficient then the ERC-32SC, with some even being dual core processors. They are known as the LEON-2 and the later LEON-3. LEON2 has a 5-stage pipeline and no SMP support, while LEON3 increases the pipeline to 7-stages and adds SMP support. LEON3 is also a VHDL core able to be added to many ASICS/FPGAs (LEON2 is a hard core). The Solar Orbiter also has both LEON2 and LEON3 processors on board as well…

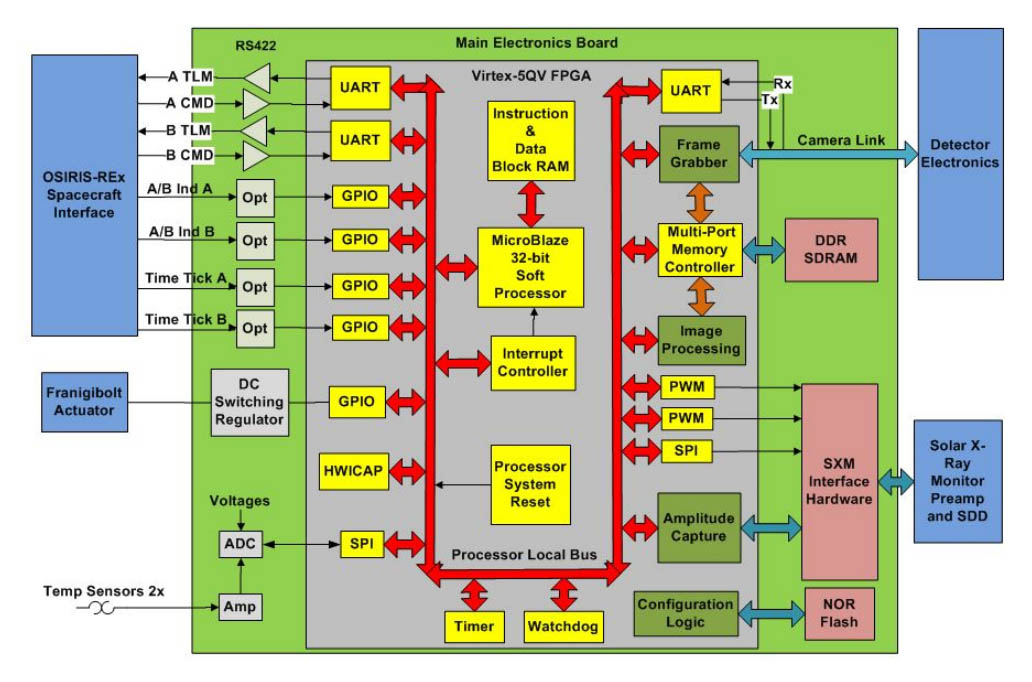

The Solar Orbiter caries with is 10 different scientific instruments, and each of them has their own processing subsystem, 9 of which are powered by LEON SPARC processors. Its common for the main processor of a spacecraft to be the most powerful, but in this case the instruments each possess their own processor more powerful then that of the main spacecraft computer. This is in large part due to many of these instruments being designed well after the original spacecraft bus and systems were baselined. Payloads can be added/changed much later in the design of the spacecraft allowing their designers to use more modern computers.

| Instrument | Processor(s) | Notes |

| Solar Orbiter OBC | ERC-32SC – Atmel TSC695 | Spacecraft Platform Processor |

| SoloHi | LEON3FT – Microsemi RTAX2000 FPGA | |

| MAG-IBS/OBS | LEON3FT – Microsemi RTAX2000 FPGA | |

| RPW-SCM/ANT | LEON3FT – Microsemi RTAX4000D FPGA LEON3FT – Cobham UT699 |

Two processors |

| SWA-HIS/EAS/PAS | LEON2FT – Atmel AT697F | up to 100MHz |

| EPD-SIS | LEON2FT – IP Core | |

| STIX | LEON3FT – Microsemi RTAX2000 FPGA | |

| EUI | LEON3FT – Cobham UT699 | 66MHz Single core |

| METIS | LEON2FT – Atmel AT697F | |

| PHI | LEON3FT – Cobham GR712RC | Dual core up to 100MHz |

| SPICE | 8051 + FPGA | Long live the MCS-51 |

There is also likely more processors on this mission as well, but it can be hard to track them all down, nearly every system has its own processing (star trackers, radios/ attitude control etc)

So as you watch the launch tonight, and perhaps see science/pictures from the Solar Orbiter (or just benefit from its added help in predicting solar storms and allowing us here on Earth to prepare for them better) think of all the SPARCs it has taken to make it function.

Tags:

Space.ESA.NASA.SPARC

Posted in:

Processor News, Uncategorized