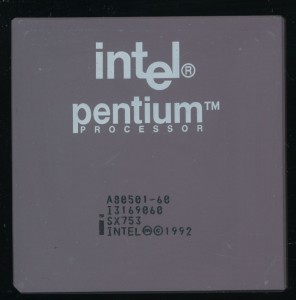

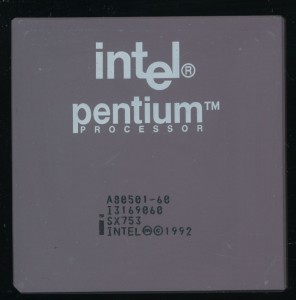

Intel A80501-60 SX753 – Early 1993 containing the FDIV bug

In 1994 Intel had a bit of an issue. The newly released Pentium processor, replacement for the now 5 year old i486 had a bit of a problem, it couldn’t properly compute floating point division in some cases. The FDIV instructions on the Pentium used a lookup table (Programmable Logic Array) to speed calculation. This PLA had 1066 entries, which were mostly correct except 5 out of the 1066 did not get written to the PLA due to a programming error, so any calculation that hit one of those 5 cells, would result in an erroneous result. A fairly significant error but not at all uncommon, bugs in processors are fairly common. They are found, documented as errata, and if serious enough, and practical, fixed in the next silicon revision.

What made the FDIV infamous was, in the terms of the 21st century, it went viral. The media, who really had little understanding of such things, caught wind and reported it as if it was the end of computing. Intel was forced to enact a lifetime replacement program for effected chips. Now the FDIV bug is the stuff of computer history, a lesson in bad PR more then bad silicon.

Current Intel processors also suffer from bad math, though in this case its the FSIN (and FCOS) instructions. these instructions calculate the sine of float point numbers. The big problem here is Intel’s documentation says the instruction is nearly perfect over a VERY wide range of inputs. It turns out, according to extensive research by Bruce Dawson, of Google, to be very inaccurate, and not just for a limited set of inputs.

Interestingly the root of the cause is another look-up table, in this case the hard coded value of pi, which Intel, for whatever reason, limited to just 66-bits. a value much too inaccurate for an 80-bit FPU.