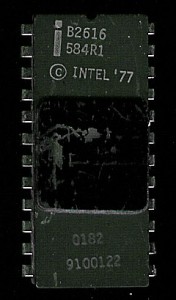

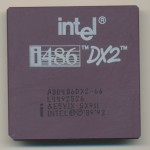

Original Intel 6MHz 80186 Made in 1984

2012 marked the 30th anniversary of the introduction of the Intel 80186 and 80188 microprocessors. These were the first, and arguably only, x86 processors designed from the beginning as embedded processors. It included many on-chip peripherals such as a DMA channels, timers and other features previously handled by external chips. Initially released at 6MHz, clock for clock many instructions were faster then the 8086 it was based on, due to hardware improvements.

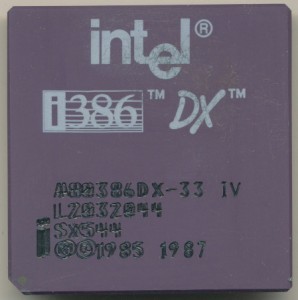

In 1987 Intel move the 186 to a CMOS process and added more enhancement including math co-processor support, power down modes and a DRAM refresh controller. Speeds were increased up to 25MHz (from the 10MHz max of the NMOS version). Through the years Intel continued to developed new versions of the 186 with added features, lower voltages, and different packages. It was not until 2007 that Intel finally stopped production of the 186 series. It continued to be made by others under license including AMD, who made versions running up to 50MHz. Fujitsu and Siemens also produced the 186 series. Like the 8051 the 186 gained significant support, being embedded in millions of devices. The instruction set was familiar, debugging and development systems were (and are) plentiful so the 186 core continues to be in wide use.

As IC complexity and transistor counts increased the need for a processor core that could not just be embedded into a system, but be embedded into a custom ASIC or SoC became apparent. IC’s were being designed to handle things like DVD playback, set-top boxes, flat panel control and more. These applications still required some sort of processor to handle them but having to have a separate IC for it was not economical.

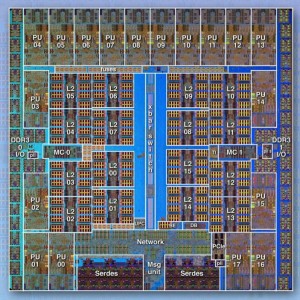

pixelworks PW166B – 67MHz Tubro186 based Flatpanel Controller made in 2004

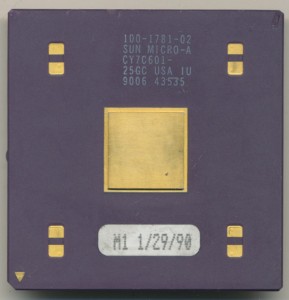

VAutomation (founded in 1994) designed Verilog and VHDL synthesizable cores (meaning they could be ‘dropped’ into an IC design or FPGA). In November 1996 VAutomation licensed the 8086/8, 80186/8 and the CMOS versions from Intel. This gave them them ability to design their own compatible models of these processors without fear of litigation. More importantly it allowed them to sub-license these designs to others. In 1997 VAutomation demo’d their first 186, the V186 core. This was a Intel 80186 compatible core that could be synthesized into a customers design. It was ‘technology independent which means it was not restricted to a certain process or even technology. It could be used in CMOS, ECL, 0.35u, 1 micron, whatever the client needed. On a 0.35u CMOS process it was capable of speeds in excess of 60MHz, and did so with less then 28,000 gates. One of the first licensees was Pixelworks, which made controllers for monitors. Typical licensing was a $25,000 fee up front and royalties on a per device basis usually split into a high volume (over 500,000 units) and low volume. Typical price per chip was $0.25-$2.00, which was cheaper then the $15 price Intel was charging for a discrete 80C186.

Read More »

In coin collecting often times an example is valued not because of its perfection, but because of its imperfections. An off-center print, the obverse being printed upside down, or the double strike, where a coin doesn’t get cleared form the die and gets hit twice.

In coin collecting often times an example is valued not because of its perfection, but because of its imperfections. An off-center print, the obverse being printed upside down, or the double strike, where a coin doesn’t get cleared form the die and gets hit twice.