A Sampling of Sample Processors

During the development of most any given processor many chips are produced before it is released for commercial use. These pre-production chips serve a wide variety of purposes in the design and debugging of the processor to ensure that the final CPU work well, sells well, and is compatible with all the vendors parts (motherboards, cooling solutions, power supplies, etc). These chips are generally referred to as samples, and there is several types of them. We’ll use Intel/AMD as the main examples but most all processor companies work in similar ways.

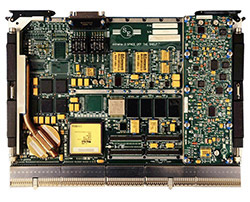

When a processor design is first being developed, the package for it is also often being developed as well, what will the new processors silicon die reside in? How many pins? How will it dissipate heat? This type of testing is often handled with Mechanical Samples. Mechanical Samples are exactly as they sound, they test the mechanical aspects of the processor, the physical fit of it. THese are often sent to board/socket manufacturers to ensure the processor will fit in sockets/boards, and with the automated equipment used to build systems. Cooling solution companies may also receive these to test how a heatsink fits on the CPU. Mechanical samples may not contain a die at all, or may be chips that were tested as bad, or simply just untested chips (Intel used a lot of untested Mechanical Samples in their educational kits).

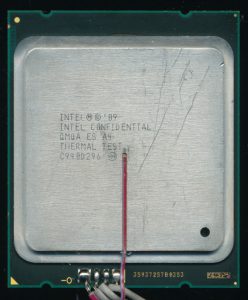

The next samples typically made are Electrical/Thermal Samples. These again do not have an actually processor die in them, but electrically do work. Electrical/Thermal samples are used to test the power draw and heat dissipation of a processor. They often use a daisy chain transistor design, which serves to draw/dissipate power. If a processor is expected to dissipate 135W of heat, a Thermal sample can be made to draw/dissipate exactly that. These can test the the power supplies on motherboards, as well as the heat dissipation abilities of cooling solutions. Some Thermal Samples have a temperature sensor added directly to the package to help see what temps they achieve. Electrical Samples and Thermal Samples could also be used as purely Mechanical Samples too, and this is sometimes seen marked on the sample.

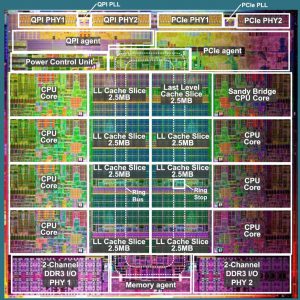

The first samples made that actually contain a functioning processor die are Engineering Samples. Engineering Samples (also known as ES) are the most well known samples. Overclockers often like to find ES CPUs as they will often allow for easier overclocking due to some not having locked in speed (multiplier locked). Engineering Sample CPUs themselves come in several types as well. Usually the first run is known as ES1, these can be thought of as an ‘Alpha’ version. They are very likely to be buggy, and rarely run at the same speed as a production chip would. These exist to test the overall processor design, or some subset of it. Some are made to test just one part of the CPU, for example , the memory controller, or the cache. Later versions of

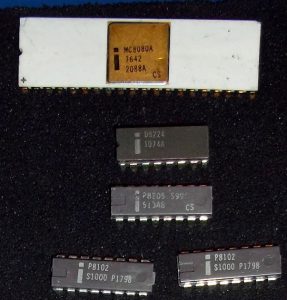

Engineering Samples are often called ‘ES2.’ These processors are getting closer to final production and are a lot less buggy, these would be considered ‘Beta’ Samples. Most of the time these are quite usable chips, and often are very similar in clock speed/features to a production processor. Intel denoted these chips with a Q-spec (such as QBGC) rather then production processor having an S-spec (such as SL5G8). AMD typically uses part numbers starting with ‘1’ for ES1 CPUs and ‘2’ for ES2 CPUs. (such as Opterons 1S160805L4BGC or 2S16….). Other companies have similar methodologies. Motorola (Freescale) used the PPC prefix for most ES CPUs and Texas Instruments uses ‘TMP’ (not to be confused with Toshiba who also uses the TMP pre-fix, but for processors in general). Once a company is fairly confident a design is ready for release one final version is made.

These are known as Qualification Samples (QS). QS processors almost always have a one to one equivalence with a production part, since that is their purpose, to make sure the design is ready for release. These processors are by far the most widely made chips, as they are shipped by

the thousands to vendors, system builders/integrations, and even the media outlets for review. The hope is that nothing major wrong is found with them, and that any bugs that are found can be dealt with in software or firmware, not requiring an entire silicon fix. Intel continues to use Q-specs for these as well, leading to some confusion with the previously mentioned ES CPU’s. AMD usually uses part numbers beginning with ‘Z’ for QS CPU’s and like Intel, does not offer these CPU’s for sale to the general public, they are either given to vendors, or sold exclusively to them for testing. Motorola uses XC, or XPC for these, and unlike AMD/Intel, mass produces these and sells them, often for years, before they decide that a part/design is truly fully qualified/characterized (in which case the prefixe is changed to MC. or MPC). Texas Instruments uses the ‘TMX” prefix for their Qual. Samples. and tended to make/sell them like Motorola did with theirs, changing the prefix to TMS for fully qualified production parts.