The Story of the Soviet Z80 Processor

Before we get into the fascinating story of the Soviet (specifically the Angstrem) Z80 clone it’s good to understand a bit about the IC industry in the USSR. There were many state run institutions within the USSR that were tasked with making IC’s. These included analogs of various western parts, some with additional enhancements, as well as domestically designed parts. In some ways these institutions competed, it was a matter of pride, and funding to come out with new and better designs, all within the confines of the Soviet system. There were also the various Warsaw Pact countries (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania), that were aligned with the USSR but not part of it. These countries had their own IC production, outside of the auspices and direction of the USSR. They mainly supplied their own local markets (or within other Warsaw Pact countries) but also on occasion provided ICs to the USSR proper, though one would assume an assortment of bureaucratic paperwork was needed for such transfers.

Before we get into the fascinating story of the Soviet (specifically the Angstrem) Z80 clone it’s good to understand a bit about the IC industry in the USSR. There were many state run institutions within the USSR that were tasked with making IC’s. These included analogs of various western parts, some with additional enhancements, as well as domestically designed parts. In some ways these institutions competed, it was a matter of pride, and funding to come out with new and better designs, all within the confines of the Soviet system. There were also the various Warsaw Pact countries (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania), that were aligned with the USSR but not part of it. These countries had their own IC production, outside of the auspices and direction of the USSR. They mainly supplied their own local markets (or within other Warsaw Pact countries) but also on occasion provided ICs to the USSR proper, though one would assume an assortment of bureaucratic paperwork was needed for such transfers.

This resulted in some countries developing similar devices, at rather different times, or different countries focusing on different designs. East Germany was all in on the Z80, Romania, Poland and Czechoslovakia made clones of the 8080, Bulgaria, the 6800 and 6502. They were though, seperate from the USSR’s own institutional system, so while East Germany had a working Z80 in the early 1980’s the USSR did not. It is this distinction we will focus on today

This article is largely from guest author Vladimir Yakovlev, translated from Russian, and edited/expanded by me.

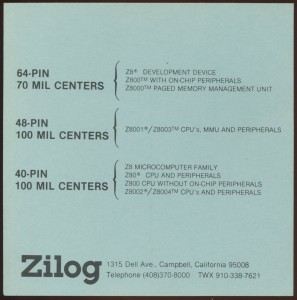

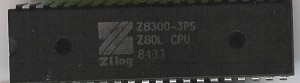

By the end of the 80s – beginning of the 90s, clones of the British Sinclair ZX Spectrum computer, a simple, cheap computer with a huge library of games originally released in 1982, were being distributed in the USSR. The “strapping” of the central processor instead of the original ULA microcircuit was done on small logic microcircuits of the 555 (74LS) series and the like, but the Z80 itself had to be bought from abroad. Naturally, the thought arose, to start making the processor yourself. After all, the processor itself, developed in 1976 for the microelectronic industry, was not too complicated.

In 1990, the development of an analogue of the Z80 was organized in Zelenograd near Moscow at the Scientific Research Institute of Precise Technology (NIITT) and the “Angstrem” plant. Initially, Zelenograd was conceived as a center of the textile industry, but was later reoriented to the development of electronics and microelectronics by Nikita Kruschev after he visited Silicon Valley (California, USA) in 1959. To this day, Zelenograd has retained the status of a scientific center and the informal name “Russian Silicon Valley”.

The chief designer was appointed Yuri Otrokhov, who had previously led similar developments. Otrokhov, who served as a tanker in his youth (military service being mandatory in the USSR), called the project the T34 microprocessor.

Otrokhov: “T-34VM1 is the internal designation of the KR1858VM1 processor, assigned by me at the stage of development and production in honor of my first tank, on which I learned to drive.”

Here is one of the versions of the creation of the clone, outlined by one of the employees of NIITT at that time, Boris Malashevich [1]:

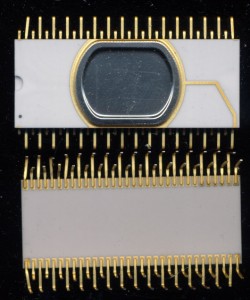

“Otrokhov, like his colleagues in the department, knew how to develop original microprocessors, but they had not yet had to reproduce analogs. Therefore, the developers included specialists from NIITT divisions who are able to restore the electrical circuit of the IC according to its topology. For 9 months after four iterations, they managed to make an NMOS microprocessor T34VM1 (KM1858VM1, KR1858VM1) – a complete analogue of the Z80A microprocessor, to be made using a 2-micron technology” (The original Zilog version was on a 4 micron process).

While Otrokhov and his team worked at Angstrem to make a NMOS Z80, a similar team was working at ‘Transistor’ in Minsk Belarus to make a CMOS version, later known as the KR1858VM3.

Due to the incredible popularity and demand for the Z80, many analogue manufacturers worked without a license, so in total less than half of all Z-80 produced were licensed products from Zilog or its official partners (SGS, Mostek, etc).

From an interview with the creators of the Z80 [2]:

Faggin: Yes, we were concerned about others copying the Z80. So I was trying to figure what we could

do that that would be effective, and that’s when I came across an idea that if we use the depletion load

the mask that doesn’t leave any trace, then I could create depletion load devices that look like

enhancement mode devices. And by doing that we could trick the customer into believing that a certain

logic was implemented, when it was not. Then I told Shima, “Shima, this is the idea how to implement

traps. Put traps, you know, figure out how to do the worst possible traps that you can imagine,” and then

Shima with his mind, that was steel mind, was able to actually figure out a bunch of traps that he could

talk about.

Shima: I didn’t count [on] talking about that mostly. I placed six traps for stopping the copy of the layout

by the copy maker. And one transistor was added to existing enhancement transistors. And I added a

transistor looks like an enhancement transistor. But if transistors are set to be always on state by the ion

implantations, it has a drastic effect on very much. I heard from NEC later the copy maker delayed the

announcement of Z80 compatible product for about six months. That is what I got from NEC. And finally

a total transistor of Z80 became 8,200 while a total of transistor of 8080 was 4,800.

In the course of the design, due to the fact that the development team had specialists in both the creation of new ICs and the reproduction of analogs, Zilog’s tricks aimed at copy protection were identified and decrypted. For example, the topologist saw the 3-Input-NAND Gate element, but this element worked as 2-Input-NAND Gate. The topology and layout of the resulting clone was different, but the functionality did not differ from the original. At first, it was possible to identify such traps, making sure that the circuit was inoperable, only by examining the circuit elements inside the die using probe analyzers. But, having understood the principle of constructing traps, a mechanism for their detection was also developed. As a result, it was possible to make a full-fledged analog of the Z80, although the electrical circuit and topology of the T34MV1 had some differences.

The German Connection

Posted in:

CPU of the Day